Brazil: “How things have (and haven’t) changed”

by a group of militants

January 20191

“You can even pacify, but the comeback will be grim”

MC Vitinho2

“Look at how things have changed”, said a comrade one of these days, “a few years back, if you were in a bakery, at a bus stop, and you heard someone complaining about the government, it was exciting. We would see an opening to talk about politics, a flash of class consciousness. Not long ago, it all started to change. Today, if I hear someone complaining, I stay alert: ‘probably the guy supports Bolsonaro…’”

1.

In the opinion of Lula, “this country hasn’t been understood since what happened in June of 2013”. A few months before being arrested, he declared: “it was premature to assume that what happened in 2013 was democratic”3 Naturally, the militants involved in that wave of protests didn’t receive this statement well: “there again, the Workers Party (PT) attacking June 2013!”

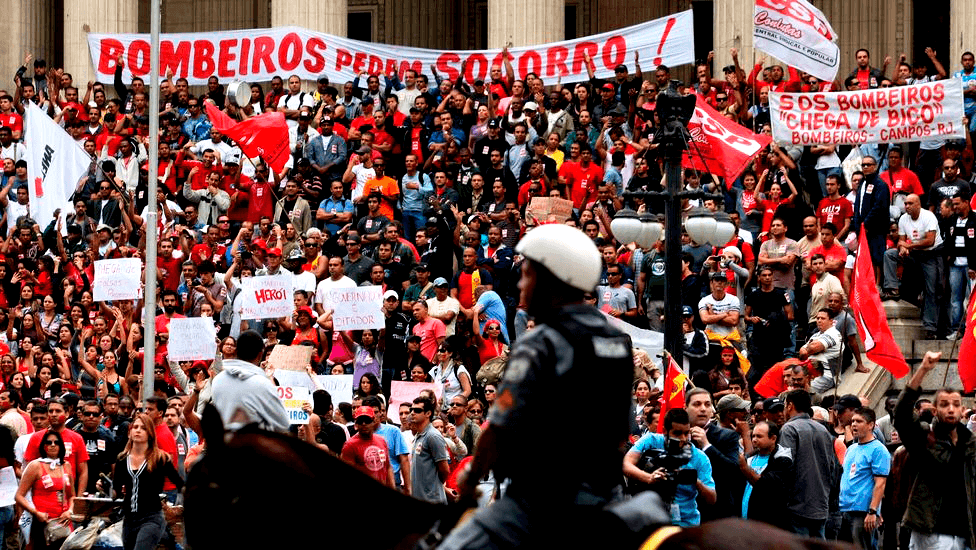

Was Lula wrong, though? Was June of 2013 really “something democratic”? In that decisive month, thousands – and afterwards, millions – of people blocked streets and highways throughout the entire country, confronted the police, set buses on fire, attacked public buildings and pillaged stores. The transport fare reduction wasn’t open to debate and negotiation, it was a demand imposed by means of force: “Either the fare goes down or the city stops!”. That doesn’t sound exactly “democratic”… It was a disruptive movement, a revolt4 that confronted the established order5 – the arrangement wrought in the redemocratization period, fixed in the 1988 “Citizen Constitution”, and which for two decades guaranteed socially acceptable standards of stability and predictability to Brazilian politics.

It scared. Amidst the largest popular mobilization in the history of this country, we caught ourselves perplexed: if we tear the democratic order down, what might happen? The revolution was not in the horizon. At that moment, the Left found itself deeply connected to the regime. Not only because it was in charge of the government; but also because, since the end of the 1970’s, “building the democracy” had become its ultimate goal.

Since 2013, the Left has fled the revolt and did it while hoisting the flag of democracy. On one side, it could claim that the protests were dangerous to the democratic order and justify the political repression6; at the same time, it could praise the protests and frame them within this very order – by thinking of June as a movement demanding “more rights” and “more democracy”, it concealed the concrete and contestatory content of these protests. The struggle against the 20 cents raise has not only touched upon a crucial aspect of the material conditions of life in the city, but also exposed the limits of the participation channels that were being developed and refined by the last few government administrations. The violence that took the streets left the democratic discourse out of place.

This becomes visible if we notice that since then, this persistence in defending the Democratic State of Law has only brought us the right to loose rights. And it wouldn’t take long before the “Law and Order Warranty Operations”7 turned against the very government that passed the Anti-terror Law.8

Since the Left identified itself with the order, contestation passed to the opposite field. It was the Right that took the masses to the streets to take down an government (and inverted symbols and practices commonly used in June 2013 transmuting, for example, MPL [Free Fare Movement] to MBL [Free Brazil Movement]9). It didn’t lose time worried with “defending the democracy”: to attain it’s political goals, it knew how to use the institutions and tactically deal with it’s limits10. By coordinating maneuvers inside the State – within the parliament, the judiciary and even inside the army – and outside of it with street mobilizations, it rose to power surrounding it from beneath and above, resembling the “tweezer movement”11 once aimed at by the Left. As Paulo Arantes put it, this new Right has revived “politics as struggle, and not as management”12.

At the presidential elections of 2018, Bolsonaro ran against Haddad, the same mayor we faced in São Paulo in June 2013. And also the elected president frequently attacks the mystics of democracy. He is politically incorrect, i.e. he won’t conform to the decorum cultivated by the rest of the actors of the political game. From a webcam in his apartment, he made statements affronting human rights, and questioning the electronic ballot box and the Constitution. By saying what cannot be said, he mocks the consensus which had being constituted since the redemocratization, exposing its false bottom and, precisely, mobilizing the revolt against it. To the defenders of the arrangement attacked by Bolsonaro, it may be reassuring to believe that the new president has been elected based on lies and dissimulation (manipulating WhatsApp users with a fake news industry); however, it seems correct to consider the opposite overall, it was by openly assuming hitherto dissimulated truths that the Captain [Bolsonaro] gathered such great popular support. But, here, the contestation of social violence doesn’t point to a horizon of transformation – instead, it lowers all expectations at once. Hypocrisy gave way to cynicism: the world is unfair, will go on being unfair, and to whom complains, it will only get worse.13

During the election campaign, the Left spoke against the dictatorship. The problem is that in practice it would “talk against the dictatorship [only] to defend the current order. Well, here is a good way to make people consider the dictatorship a possibility”14. When the forces that once criticized social injustice became themselves the administrators of this injustice, we get a short circuit: the power of contestation of order is transferred to those who now expose violence and suffering by assuming them cynically – not to question, but to ratify them. This is how the very perception of a torturing everyday life can be converted into the justification of torture: “People left unattended in hospital queue lines, that is torture! Fourteen million people unemployed, that is torture!”, argued an elector of Bolsonaro from the far south of São Paulo, soon after the balloting.15

The rebelliousness channeled by the Right is paradoxical: it contests the current order while drawing on and promising to harden it – which reminds us of how João Bernardo16 defines fascism: a revolt within the order. If we can, today, speak of a fascist movement, it wouldn’t be due to the authoritarian characteristics of Bolsonaro or to its hate speech, but rather to the breeding ground of revolted people that feeds it.17

2.

Compared to classic fascism, the ongoing conservative revolt seems yet somewhat diffuse. However, to say that we are not dealing with a fascist movement doesn’t mean the scenario is more soothing. Afterall, the Workers Party (PT)’s “way of govern” has also been quite distant from the social democrat experiences from the beginning of the last century.

The social democracy – which proposed, in exchange for an alliance with the capital, a programme of structural reforms and the expansion of universal rights – can barely be compared to the administrations of PT, which were limited to combining market expansion with public policies focused on specific segments of society. And yet, they have constituted an efficient engineering of social conflict management, incorporating the workers’ organizations into the government’s means. The strategy of “accumulation of forces” adopted by the brazilian Left has meant, in practice, the conversion of the grassroots movements which began in end of the dictatorship period into forces of production of the new social arrangement.

The pacification project continuously improved during the PT administrations represented, in fact, a permanent war18 – visible not only in the growing rate of evictions, incarceration, killings, torture and police lethality, but also in labour. Along with the repressive devices of exception, the motor of our “emerging economy” was a true ” state of economic emergency”19, in which the social calamity would justify the dictated politics dictated by urgency. Under the discourse of “broadening of rights”, multiple forms of subemployment were spread, with weary routines and uncertain incomes, vulgarly known as “shitty jobs” or “fucked up job vacancies”20.

The future promised by programmes that grant access to microcredit, home ownership or higher education, or promised by the increase in (formal or informal) employment rates, dissipated into a perpetual present of double shifts, debt, competition, insecurity, tiredness in queues, humiliation in crowded buses, depression and mental exhaustion. The price for the euphoria of the Lula and Dilma administrations was, overall, a total mobilization for survival, translated as bigger and denser portions of life spent working.

By means of all sorts of instruments, this managerial regime made the capitalist mesh in Brazil denser and deepened the proletarization process in multiple strata and corners of the country. The so called “inclusion policies”, as well as the vertiginous process of “digital inclusion” that reached the previously unconnected masses, or even the infrastructure projects which opened new routes for the circulation of capital, included populations and territories in increasingly intense exploration circuits and provided, in this way, more fuel to the furnaces of flexible accumulation. All of that with high approval ratings!

The events of 2013 broke the peaceful environment produced by all that euphoria. The wave of protests that took the Brazilian cities brought the war up, signalling the crisis of this once successful model of managing social conflict. The revocation of the 20 cents bus fare raise wasn’t enough to fix the problem: it wasn’t possible anymore to dissipate that popular animosity and reestablish the magical formula of consensus. The attempts to bring the harmony back – the “five pacts in favor of Brazil”, for example, that Dilma announced in television by the end of the period of protests – were all in vain. The continuity of the armed pacification would depend, thus, on a novel arrangement.

Once called upon to “neutralize the opposing forces” which appeared in June 2013, the agents of order, which had been for years in Haiti [leading the Minustah, UN’s “Peace Operation”] and in Rio de Janeiro favelas accumulating know-how, didn’t seem to be leaving the scene. It is clear today that these devices of repression weren’t specific to those events. In the new management strategy that emerges in face of the threat of social chaos which showed up in 2013, the tactics of war – along with its commanders – are openly playing a central role.

In this rearrangement, “Jair Bolsonaro is an inexact”, yet potent, “name [for a new rationality that is underway] exactly because he was able to combine the escalation of repression with the social rebelliousness set to motion in 2013. Two paths converge in him:

The first [gear], the maintenance of law and order and the promise of the empire’s security and that every opposing heart beat will be violently suppressed. The second gear operates upon the illusion of rupture and the rapture of revolt: “everything will be different, like the old days” or “that’s got to change”.21

If the protests spread a revolt against the established order, restoring it would depend on mobilizing this very sentiment. In this process of recuperation, not only the repressive forces were set in motion: the workers’ own contestation energy was directed against themselves. The perspectives of restoring peace, already politically compromised, faces now also economic barriers – with the crisis, the efficiency of the popular participation devices and social programs is compromised. This is when social animosity begins to seem functional: since there is no more money, everyone might just as well kill themselves while struggling for crumbs of bread. Confrontation and revolt cease to be a threat to the established order and become a new kind of discipline.

When in 2015 and 2016 the new Right paraded on Avenida Paulista, the sociologist Silvia Viana22 noted that the dimensions of that indignation against corruption could be connected with the ongoing experience in the job market. What would the “green-and-yellow” hatred see in common, she would ask, between such different targets as the corrupt politician, the racial quota beneficiary, the housing movement, the burglar, the beggar and the scholarship holder? All of them jump the queue. They take advantage of shortcuts and protections in the fight for survival, they appeal to advantages which lead to unfair competitions, in the arena where each one should be fighting by itself.

In the context of economical exhaustion, the new Right gave a political form to the increasing competition between workers. By assuming without restraints the “law of the jungle”, it devised an action plan adequate to the level of savagery reigning the world of labour gestated in the past few decades. Survival depends on individual resilience and willpower, and any kind of assistance should be seen as “victimization”. It shouldn’t then be surprising the popular appeal of gun carriage liberation laws: it would be your chance to shoot your competitor – the guy that cut you off in traffic, that screwed you in your company, that stole your place at university. Is there a candidate more adequate to the war of all against all then the Captain?

But Jair Bolsonaro is “an inexact name” precisely because this phenomenon is not exclusive to the Right: the increase of competition between workers cuts through the whole political spectrum, taking different colours, even seemingly opposite ones. For example, both virtual lynchings promoted by conservative groups against allegedly “communist” teachers and the escrache23, which gained strength as a feminist practice over the last years, operate in a very similar manner. Besides destroying the reputation of the one being denounced, both often aim – and in many cases are successful – at making the person lose his job. In this social environment filled with competition, identities present themselves as trenches for the dispute. Seen by this angle, one understands both the appearance of market strategies such as “afro-entrepreneurship”, and the recent growth of a part of the black movement which abandons the racial autodeclaration principle and demands the creation “racial truth evaluating committees” and “phenotypic criteria” to prosecute and expel colleagues that benefited from racial quotas in public tenders or university admittance exams.24

Today’s identity politics movements were mainly promoted by targeted social policies (all sorts of quotas, cultural incentive laws, special secretariats for minorities, etc), however, it does not follow from them automatically, but constitute a new phenomenon. The punitive, authoritarian and excluding traces of these movements reveal a belligerent tendency, which throws the tolerant coexistence and expectations of inclusion cultivated by the consensus politics out. Accelerating social disaggregation, the deepening of the crisis narrowed the possibilities of managing conflict. At the same time, it accentuated the confinement of politics to the dimensions of urgency and immediacy. Both to the Left and to the Right, these novel social actors have in common the will for a sterile confrontation, which lacks the horizon of changing social reality.

As politics and open war become more and more alike, the technologies of social mediation developed in the course of the last years seemingly become obsolete. Despite their efforts to prove themselves capable of dealing with the requirements of a recession period, implementing austerity measures, the managers of PT ended up being themselves targets of the destructive movement of the crisis. The wave of destruction which fell not only upon the main operators of the political arrangement constituted since the redemocratization period and their government machinery, but also upon some of the biggest brazilian companies, must be comprehended within the frame of a “forced annihilation of a mass of forces of production”25, typical movement of capitalist crises, which always comes accompanied by an increase of exploration. The destruction of productive forces, often by means of war, has always been an efficient emergency exit to capital.

3.

On this side of class struggle, the known paths have only taken us to dead ends.

In the successful years of left-wing administrations, economic growth was combined with the integration of popular movements to the capitalist regime, in a complex political participation and social pacification engineering, which would efficiently put limits to every horizon of real contestation. In that context, the appearance of revolts of young workers who would paralyze cities, confront the police and force governments ran by different political parties to reduce the fares of public transport was somewhat unusual. Popping out throughout the country since the “Revolta do Buzú” [something like “revolt of the bus”] – which shook Salvador already in 2003, the first year of Lula’s presidency – these uprisings pointed to breaches in the “monotonous paralysis” of the period:

For the small groups to the left and at the margins of the government, to trigger the disorder of revolt meant the possibility to face that giant structure of class struggle management. The violent political explosion in the streets rejects the mechanisms of participation and reacts to the armed repression. (…) revolt appears precisely as destructive critique, as the negation of an immobilizing consensus.26

Only by means of rupturing consensus social conflict could overcome the narrow limits of administered routine and openly break out as class struggle. From this point of view, the possibility of contestations was alive in the movements of disruptive character which, by making war visible, were in practice critiquing the armed enforcement of peace. Besides the revolts concerning public transportation, this was manifested in the wildcat strikes in the mega constructions of PAC (“Growth and Acceleration Program”) – the front of national capitalism expansion (“not a strike, but terrorism”, explained a worker from Jirau)27; in the dissident landless workers that, in spite of MST (Landless Workers Movement) opposition, occupied the Lula Institute headquarters28; in the wave of spontaneous urban land occupations that spread throughout the suburbs of São Paulo under mayor Haddad’s municipal administration29; in the vertiginous increase in the number of strikes since 2012 – reaching, between 2013 and 2016, the highest peak ever registered [more than 2.000 strikes each year] – and in the growing rebelliousness of these strikers against their unions30; last, in the collective rejection of austerity measures by secondary students, repelling any mediation coming from student unions by directly occupying their schools, forcing the government to retreat in its attempt to close schools.

As the cracks in the consensus become deep fissures, the meaning and direction of these struggles are nonetheless displaced and lose their power of contestation. The conflicts become part of the everyday agenda and the revolt conforms itself into a mere device of the new political arrangement. Our bet in the rupture of consensus was exhausted alongside with it, disorienting altogether the formulations that once came from it. Since then, the social violence that erupted now seems to point toward chaos and an urge for competition rather than anything else. It is, after all, what was underlying the structures of pacification: disaggregation of the social fabric lacking any horizons for collective action.

Innumerous voices were raised in response to the trace of destruction of 2013, advocating at once the necessity of resuming the rank-and-file work. The limits of the revolt tactics would be explained by the lack of mass organizations, structured in workplaces, neighborhoods, and places of study. Well, these organizations already existed! In fact, they were part of the governmental machinery against which the protests were uprising: the left-wing party running the federal government was present in directories in all 5570 cities of Brazil; the two most important national trade unions supported the government; the largest rural landless workers movement in the world and a number of housing movements became the operators of social programs and agencies of entrepreneurship; an ambiguous mass of popular associations, NGO’s, cultural collectives, and periphery groups had their reproduction attached to funding systems based on open call forms, of different types and which granted different amounts of money.31 All of these were fed by a myriad of registrations, databases and mappings made by all sorts of private and state-owned organs – including, of course, the police institutions.32

This is not a deviation: “at rank-and-file level there could subsist only objectified contingents of workers, duly registered and represented – treated as currency in the trading of bureaucracies”33. Realizing this dynamic in the 90’s, a leader from the landless movement synthesized: “people in protest, money with interest”. To have an “organized social basis” [or an organized rank-and-file] means, effectively, to manage populations. The “grassroots organisation” done by these movements wasn’t abandoned, but taken to it’s ultimate consequences, establishing itself as a managerial technique.

Sem isto a gestão se tornaria impraticável. (…) Daí as concessões materiais enquanto lastro econômico que garante a operacionalidade e ossificação dos movimentos sociais, sua conversão em braços do Estado encarregados de cadastrar a base social e gerir os parcos recursos das políticas públicas, portanto órgãos que cumprem tarefas essenciais para o sucesso da contrarrevolução permanente em seu modelo democrático-popular.34

From this point of view, the Left’s claim to “politically organize the quebradas [poor neighbourhoods from the urban outskirts]” after June 2013 seemed like a farcical attempt to reenact history, as if it was possible to recover the supposed long lost purity of left-wing ecclesiastical community organising in the 70’s and 80’s. On the other hand, it was a way of escaping the problem laid by the street riots in 2013: anonymous and explosive, that revolt was the expression of an urban proletariat whose labour power was developed through a variety of public policies, connected to the technologies of information, employed in precarious and highly unstable and mobile conditions (in this sense, the centrality of transportation in its demands is not casual).

Today, however, the revolt seems to merge itself with the established order. When in mid 2018 a decentralized movement of truck drivers put halt to the Brazilian economy by blocking highways all over the country, the interests and organization of workers appeared mixed with corporate ones. The very rebellion that managed to put the country on the verge of collapse had as its horizon, precisely reinforcing the order, as it cried for “military intervention”. The truckers’ stoppage conquered great popular support, influencing some sectors of urban workers (from motorcycle couriers to teachers)35 and sealed the coffin of the “great national agreement”36 attempted by Temer’s administration – an attempt, already lowered, to guarantee the survival of the old political arrangement around an austerity program.

At last, Bolsonaro’s victory ties the line of continuity between 2013 and 2018: the conformation of revolt to order. And facing that,

Given this picture of isolation and impotence, what most of the Left has been doing is to create antifascist and broad democratic fronts in various places, with different forms, in order to affirm leftist values against the growth of far-right values – the red and black or the colorful, against the green and yellow of the Brazilian national flag, Democracy values against Dictatorship values. (…) These positions also remain in an abstract and discursive field: what does it mean to fight fascism today with guns? Who are the fascists, our co-workers who voted for Bolsonaro?37

The new scenario corners the possibilities of formulating a critical point of view. On the one hand, the claim for rehabilitating the already crippled democratic arrangement of pacification, whose forces become each time less productive – and hence, powerless, often limiting itself to the defense of symbols. On the other hand, the mere insistence in revolt loses its contestation power, after all, it is the regime itself that now openly takes the social violence as part of itself. Immured between these two forms of defense of the order, one might wonder where does class struggle wanders.

Notes

- 1 This analysis of the current situation in Brazil was written by “a group of militants” and originally published in Portuguese under the name “Olha como a coisa virou” at Passa Palavra. The English translation was first published at Libcom.org.

- 2 MC Vitinho, Crime é o Crime / Dilma Sapatão / Instalar a UPP This song is “proibidão” (a subgenre of carioca funk connected to criminal factions from Rio de Janeiro’s favelas) recorded after the invasion of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas by the Army and the creation of the Pacification Police Units (UPP) under the Workers Party’s federal government.

- 3 Former president Lula’s speech at the “Act for the reconstruction of the democratic state” given in the halls of the UFRJ Law School (Aug 11, 2017, available here)

- 4 We speak here of “revolt” because it was the term used by the militants active in the urban uprisings against bus fares which broke out in Brazil between 2003 and 2013. On the other hand, we also take into account João Bernardo’s conception of the term, to whom “revolt is the agitation under the flag of common place, thus exactly opposite to revolution, which is the liquidation of common place” (Revolta/revolução, Passa Palavra, Jul 2013) – Distinction which, in fact, contributes to the analysis of the limits faced by these struggles.

- 5 “The only “movement demand”—the repeal of the loi Travail—was not really one, since it left no room for any adjustment, for any “dialogue.” With its entirely negative character, it only signified the refusal to continue being governed in this manner (…)”. (The Invisible Committee, Now, Ill Will Editions, 2017). This description of the protests against the new french labour law (Loi travail) made in 2016 by the “Invisible Committee” seems very familiar.

- 6 It’s worth remembering, for example, the episode when the intellectual and PT-supporter Marilena Chauí declared, in a talk to Rio de Janeiro’s Military Police, that the black blocs had fascist inspiration. See “’Black blocs’ agem com inspiração fascista, diz filósofa a PMs do Rio” (Folha de São Paulo, Aug 2013).

- 7 Translation Note: In Brazil, the “Law and Order Warranty Operations” (GLO Operations) are a legal instrument by which the President of the Republic authorizes a temporary military intervention over part of the national territory “to pacify opponent forces” (in other words, to repress civil conflicts). The GLO were used during mega-events such as the 2014 FIFA World Cup or the 2016 Olympics Game. Read more here.

- 8 Tracing the repressive escalation in the long aftermath of Rio de Janeiro’s post-june, between 2013 and 2014, the film Operações de Garantia da Lei e da Ordem (something like “Law and order operations”, Julia Murat, 2017) draws the line of continuity between Dilma’s discourse when facing the protests and Temer’s inauguration speech: the defense of order. Translation Note: the Anti-terror Law was approved by Dilma’s government just before the impeachment process.

- 9 Translation Note: respectively, “Free Pass Movement” and “Free Brazil Movement”. MPL is a radical social movement created in 2005 that reclaims free public transportation and was in the heart of June 2013 uprising (read more here). MBL is a right-wing organisation founded in 2014 that head the protests for Dilma Rousseff impeachment (read more here).

- 10 On one side, we watched the scene in which Lula, despite knowing his conviction was a political maneuver, surrendered to prison reaffirming his trust in the democratic norms: “if i didn’t believe in the Justice, I wouldn’t have built a political party, I would have proposed a revolution in this country.” On the other, we see that the Bolsonaro’s campaign summit, despite knowing the elections were already won, didn’t stop questioning the ballots’ legitimacy and affirming that the victory of their opponent could only happen due to fraud. Eduardo Bolsonaro, the son of the elected president, even mocked the Supreme Court, stating that to shut it down only “a soldier and a corporal” were needed.

- 11 Common expression in militant environments which designates the strategy planned by the so called “popular democratic” field since the 80’s. As a tweezer, seizing the power would require a twofold movement: from above, the gradual occupation of institutional spaces; from beneath, mass mobilization directed by popular organizations, social movements and trade unions.

- 12 “For the first time, what is expressed in the elections”, said Paulo Arantes recently in an interview, “wasn’t only about generating or managing classic public policies, but it was about seizing power with political confrontation”. (Abriu-se a porteira da absoluta ingovernabilidade no Brasil, diz Paulo Arantes, Brasil de Fato, Nov 2018). Translation Note: Paulo Arantes is a Brazilian marxist author.

- 13 Analysing the recently nominated Minister of Foreign Relations of the Bolsonaro administration, Jan Cenek (in Trump, o Ocidente, o chanceler, o ex-prefeito, o romance e a crise, Dec 2018) reaches similar conclusions: “the far-right programme is beyond the deaf mute reformism, because it assumes and openly defends that which the other said it wouldn’t do, but has done and keeps doing. Since capitalism is not gone, repression is inevitable, the difference being the open defense of militarization and violence by the far-right, opposed to the discursive condemnation of both of these by the deaf mute reformism, which proclaims itself as democratic (but those who were in the streets in June 2013 know well what Haddad did on that Fall).”

- 14 Emiliano Augusto, A paixão é um excelente tempero para ação, mas uma péssima lente para a análise (Facebook, Oct 2018).

- 15 Carolina Catini e Renan Oliveira, Depois do fim (Passa Palavra, Nov 2018).

- 16 Translation Note: João Bernardo is an autonomist marxist militant born in Portugal. During the Portuguese Revolution of 1974, he was member of the “Combate” workers newspaper. See his biography here.

- 17 Fascism is understood as an historical phenomenon which is not a mere synonym to exacerbated authoritarianism, as it has been used by the left. It’s worth noting that the Brazilian dictatorship from the 60’s-80’s, for example, despite being authoritarian and nationalist, wasn’t properly fascist. For an extensive discussion about this topic, see João Bernardo, Labirintos do Fascismo (3ª versão, revista e aumentada, 2018).

- 18 For an analysis about this counter-insurgency project, see “Depois de junho a paz será total” (in Paulo Arantes, O novo tempo do mundo, São Paulo, Boitempo, 2013).

- 19 This expression is used by Leda Paulani in “Capitalismo financeiro, estado de emergência econômico e hegemonia às avessas” (in Francisco de Oliveira, Ruy Braga e Cibele Rizek [orgs.], Hegemonia às avessas, São Paulo, Boitempo, 2010).

- 20 This term was popularized by a Facebook page.

- 21 O Aluminista, Sequestro da revolta! (Passa Palavra, nov. 2018).

- 22 Talk by Silvia Viana in the seminar “Alarme de Incêndio: cultura e política na época das expectativas decrescentes” (Mar 5, 2016).

- 23 Although the “escrache” has an earlier origin in the Left, referring to the struggles around Argentine political disappearances, it was amidst identity politics that it gained, in the last few years, its best-rounded form. For a more dynamic narrative of these actions, see Dokonal, Sobre escrachos, extrema-esquerda e suas próprias novelas: o conto que pensei em escrever (Passa Palavra, jul. 2014).

- 24 About this, see A caça aos ‘falsos cotistas’: austeridade, identidade e concorrência (Passa Palavra, Aug 2017).

- 25 “The conditions of bourgeois society are too narrow to comprise the wealth created by them. And how does the bourgeoisie get over these crises? On the one hand by enforced destruction of a mass of productive forces; on the other, by the conquest of new markets, and by the more thorough exploitation of the old ones” (Marx and Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party, 1848).

- 26 Caio Martins and Leonardo Cordeiro, Revolta popular: o limite da tática (Passa Palavra, May 2014). English version: Brazil: Popular Revolt and Its Limits (Published at Libcom.org)

- 27 The commentary is from a blue-collar who was recording on his cellphone images of the fire at the workers’ accommodations. The impacts of the construction of Jirau, the worker uprising and the articulation between national trade union centers and the government to repress the movement are depicted in the documentary Jaci: sete pecados de uma obra amazônica (Caio Cavechini, 2015), released in English under the name Jaci: Seven Sins Of An Amazonian Work. It’s also worth looking at the reports on stoppages, killings, tortures and prisons at the construction sites over the years made by Liga Operária, a trade union group of maoist influences that operates in the region. Available here).

- 28 The trajectory of resistance of the residents of the Milton Santos rural settlement, which during the Dilma administration was endangered with suffering a “reversed agrarian reform”, was extensively reported by Passa Palavra (the complete coverage can be accessed here). In English, see here.

- 29 In the beginning of August 2013, Passa Palavra reported a “silenced spring”: only in the region of Grajaú, “about 20 terrains were spontaneously occupied by families which no more have condition to pay rent (…). It is at least curious to note that, following the political agitations which we call the “events of june”, a process of direct struggle has been developed by the poorer in the urban sprawl and that not even the left-wing communication organs have been giving it the attention it deserves. (Ocupações do Grajaú protestam por moradia no centro de São Paulo, Passa Palavra, ago. 2013).

- 30 The annual reports on Strike Balance, published by Dieese, raise a total of 2.050 registered strike in Brazil in the year of 2013, going up to 2.093 in 2015 (until now, no reports on 2014 and 2015 strikes were published). But, as Leo Vinicius pointed out, analysing the period should take into account the “strikes and actions in workplaces made outside trade union structures, which are not computed in these statistics. It is likely that many autonomous actions of organized workers occurred without us knowing at all. (Leo Vinícius, Bem além do mito “Junho de 2013”, Passa Palavra, jul. 2018).

- 31 For a portrait of this scenario, see Estado e movimentos sociais (Passa Palavra, Feb 2012).

- 32 The case of GEO-PR (Something like “Georeferenced system of monitoring and support to Presidency’s decision”) is emblematic. Created by the Lula administration in 2005 under the pretext of protecting quilombola communities, indigenous lands and rural settlements. “Fed by data about social movements, such as ‘manifestations’, ‘strikes’, ‘mobilizations’, ‘fundiary matters’, ‘indigenous questions’, ‘NGO action’ and ‘quilombolas’”, during more than a decade, gave body to “a powerful tool of social movement surveillance, the biggest yet known” (Lucas Figueiredo, O grande irmão: Abin tem megabanco de dados sobre movimentos sociais, The Intercept, Dec 2016).

- 33 Part of the article Revolta popular: o limite da tática (cit.)

- 34 Pablo Polese, A esquerda mal educada (Passa Palavra, jul. 2016).

- 35 About the repercussion of trucker stoppages among app workers, motorcycle couriers, school bus drivers and other urban categories, see Gabriel Silva, A greve dos caminhoneiros e a constante pasmaceira da extrema esquerda (Passa Palavra, May 2018).

- 36 “Michel [Temer] forms a government of national union, promotes a great agreement, protects Lula, protects everybody. This country goes back to being calm, no one can take this anymore”, said Sérgio Machado, former president of Transpetro, in his famous conversation with the Minister of Planning from Dilma’s administration, Romero Jucá, little before the voting deciding if Dilma’s impeachment would occur (recorded and leaked to the press in May 2016, the dialogue transcript is available here).

- 37 Um outro João (“Another João”), Breve comentário sobre as frentes democráticas e antifascistas contra Bolsonaro (Passa Palavra, Dec 2018.